I’m working on some heavy NSTextView, NSScrollView, NSClipView type stuff in MarsEdit. This stuff is fraught with peril because of the intricate contract between the three classes to get everything in a text view, including its margins, scrolling offset, scroll bars, etc., all working and looking just right.

When faced with a problem I can’t solve by reading the documentation or Googling, I often find myself digging in at times, scratching my head, to Apple’s internal AppKit methods, to try to determine what I’m doing wrong. Or, just to learn with some certainty whether a specific method really does what I think the documentation says it does. Yeah, I’m weird like this.

I was cruising through -[NSClipView scrollToPoint:] today and I came across an enticing little test (actually in the internal _immediateScrollToPoint: support method):

0x7fff82d1e246 <+246>: callq 0x7fff82d20562 ; _NSDebugScrolling

0x7fff82d1e24b <+251>: testb %al, %al

0x7fff82d1e24d <+253>: je 0x7fff82d20130 ; <+8160>

0x7fff82d1e253 <+259>: movq -0x468(%rbp), %rdi

0x7fff82d1e25a <+266>: callq 0x7fff8361635e ; symbol stub for: NSStringFromSelector

0x7fff82d1e25f <+271>: movq %rax, %rcx

0x7fff82d1e262 <+274>: xorl %ebx, %ebx

0x7fff82d1e264 <+276>: leaq -0x118d54fb(%rip), %rdi ; @“Exiting %@ scrollHoriz == scrollVert == 0”

0x7fff82d1e26b <+283>: xorl %eax, %eax

0x7fff82d1e26d <+285>: movq %rcx, %rsi

0x7fff82d1e270 <+288>: callq 0x7fff83616274 ; symbol stub for: NSLog

Hey, _NSDebugScrolling? That sounds like something I could use right about now. It looks like AppKit is prepared to spit out some number of logging messages to benefit debugging this stuff, under some circumstances. So how do I get in on the party? Let’s step into _NSDebugScrolling:

AppKit`_NSDebugScrolling:

0x7fff82d20562 <+0>: pushq %rbp

0x7fff82d20563 <+1>: movq %rsp, %rbp

0x7fff82d20566 <+4>: pushq %r14

0x7fff82d20568 <+6>: pushq %rbx

0x7fff82d20569 <+7>: movq -0x11677e80(%rip), %rax ; _NSDebugScrolling.cachedValue

0x7fff82d20570 <+14>: cmpq $-0x2, %rax

0x7fff82d20574 <+18>: jne 0x7fff82d20615 ; <+179>

0x7fff82d2057a <+24>: movq -0x116a7ad9(%rip), %rdi ; (void *)0x00007fff751a9b78: NSUserDefaults

0x7fff82d20581 <+31>: movq -0x116d5df8(%rip), %rsi ; “standardUserDefaults”

0x7fff82d20588 <+38>: movq -0x1192263f(%rip), %rbx ; (void *)0x00007fff882ed4c0: objc_msgSend

0x7fff82d2058f <+45>: callq *%rbx

0x7fff82d20591 <+47>: movq -0x116d5fa0(%rip), %rsi ; “objectForKey:”

0x7fff82d20598 <+54>: leaq -0x118ab0cf(%rip), %rdx ; @“NSDebugScrolling”

0x7fff82d2059f <+61>: movq %rax, %rdi

0x7fff82d205a2 <+64>: callq *%rbx

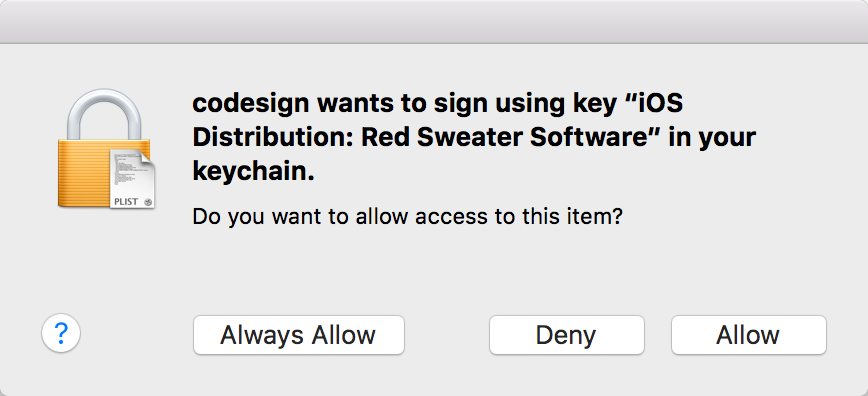

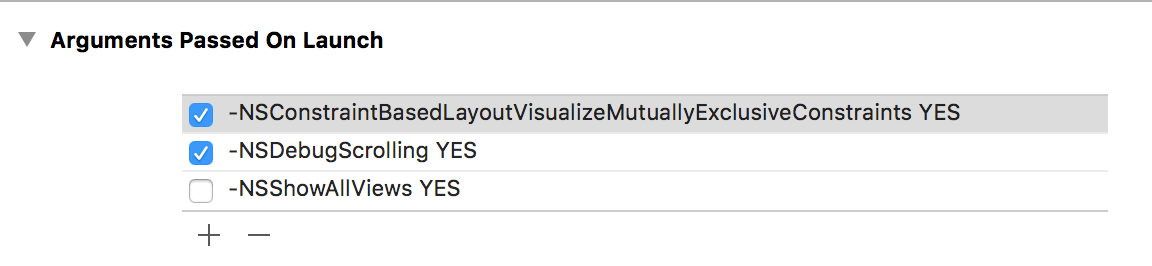

Aha! So all i have to do is set NSDebugScrolling to YES in my app’s preferences, and re-launch to get the benefit of this surely amazing mechanism. Open the Scheme Editor for the active scheme, and add the user defaults key to the arguments passed on launch:

You can see a few other options in there that I sometimes run with. But unlike those, NSDebugScrolling appears to be undocumented. Googling for it yields only one result, where it’s mentioned offhand in a Macworld user forum as something “you could try.”

I re-launched my app, excited to see the plethora of debugging information that would stream across my console, undoubtedly providing the clues to solve whatever vexing little problem led me to stepping through AppKit assembly code in the first place. The results after running and scrolling the content in my app?

Exiting _immediateScrollToPoint: without attempting scroll copy ([self _isPixelAlignedInWindow]=1)

I was a little underwhelmed. To be fair, that might be interesting, if I had any idea what it meant. Given that I’m on a Retina-based Mac, it might indicate that a scrollToPoint: was attempted that would have amounted to a no-op because it was only scrolling, say, one pixel, on a display where scrolling must move by two pixels or more in order to be visible. I’m hoping it’s nothing to worry about.

But what else can I epect to be notified about by this flag? Judging from the assembly language at the top of this post, the way Apple imposes these messages in their code seems to be based on a compile-time macro that expands to always call that internal _NSDebugScrolling method, and then NSLog if it returns true. Based on the assumption that they use the same or similar macro everywhere these debugging logs are injected, I can resort to binary analysis from the Terminal:

cd /System/Library/Frameworks/AppKit.framework otool -tvV AppKit | grep -C 20 _NSDebugScrolling

This dumps the disssembly of the AppKit framework binary, greps for _NSDebugScrolling, and asks that 20 lines of context before and after every match be provided. This gives me a pretty concise little summary of all the calls to _NSDebugScrolling in AppKit. It’s pretty darned concise. In all there are only 7 calls to _NSDebugScrolling, and given the context, you can see the types of NSLog strings would be printed in each case. None of it seems particularly suitable to the type of debugging I’m doing at the moment. It’s more like plumbing feedback from within the framework that would probably mainly be interesting from an internal implementor’s point of view. Which probably explain why this debugging key is not publicized, and is only available to folks who go sticking their nose in assembly code where it doesn’t belong.