Any great software developer must inevitably become a great software debugger. Debugging consists largely of setting breakpoints, then landing on them to examine the state of an app at arbitrary points during its execution. There are roughly two kinds of breakpoints: those you set on your own code, and those you set on other people’s code.

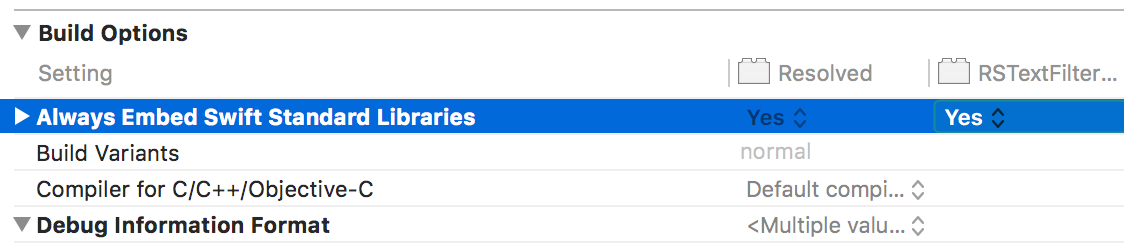

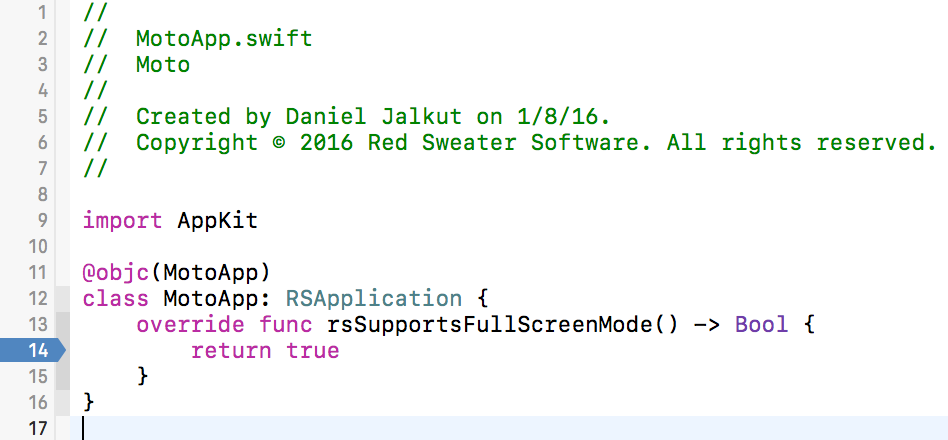

Setting a breakpoint on your own code is simple. Just find the line of source code in your Xcode project, and tap the area in the gutter next to the pertinent line:

But what if you need to set a breakpoint on a system API, or a method implemented in a drop-in library for which you don’t have source code? For example, imagine you are hunting down a layout bug and decide it might be helpful to observe any calls to Apple’s own internal layoutSubviews method on UIView. Historically, to an Objective-C programmer, this is not a huge challenge. We know the form for expressing such a method symbolically and to break on it, we just drop into Xcode’s lldb console (View -> Debug Area -> Activate Console), and set a breakpoint manually by specifying its name. The “b” shorthand command in lldb does a bit of magic regex matching to expand what we type to its full, matching name:

(lldb) b -[UIView layoutSubviews] Breakpoint 3: where = UIKit`-[UIView(Hierarchy) layoutSubviews], address = 0x000000010c02f642 (lldb)

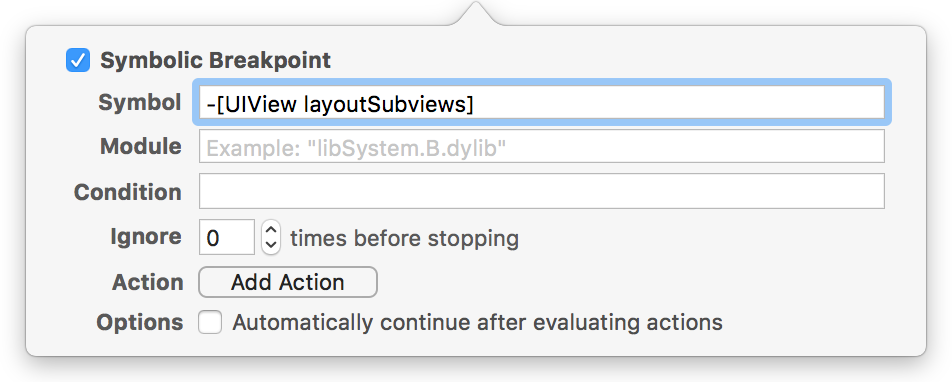

If you’re intimidated by the lldb console, or you want the breakpoint to stick around longer than the current debug session, you can use Xcode’s own built-in symbolic breakpoint interface (Debug -> Breakpoints -> Create Symbolic Breakpoint) to achieve the same thing:

In fact, if you add this breakpoint to your iOS project and run your app, I am pretty sure you will run into a breakpoint on Apple’s layoutSubviews method. Pop back into the lldb console and examine the object that is being sent the message:

(lldb) po $arg1 <UIClassicWindow: 0x7f8e7dd06660; frame = (0 0; 414 736); userInteractionEnabled = NO; gestureRecognizers = <NSArray: 0x60000004b7c0>; layer = <UIWindowLayer: 0x600000024260>>

Now, continue and break on the symbol again. And again. Examine the target each time by typing “po $arg1” into the lldb console. You can imagine how handy it might be to perform this kind of analysis while tracking down a tricky bug.

But what about the poor Swift programmers who have come to our platforms, bright-eyed and full of enthusiasm for Swift syntax? They who have read Apple’s documentation, and for whom “-[UIView layoutSubviews]” is impossible to parse, whereas “UIView.layoutSubviews” not only looks downright obvious, but is correct for Swift?

Unfortunately, setting a breakpoint on “UIView.layoutSubviews” simply doesn’t work:

(lldb) b UIView.layoutSubviews Breakpoint 3: no locations (pending). WARNING: Unable to resolve breakpoint to any actual locations. (lldb)

This fails because there is no Swift type named UIView implementing a method called layoutSubviews. It’s implemented entirely in Objective-C. In fact, a huge number of Objective-C methods that are exposed to Swift get compiled down to direct Objective-C message sends. If you type something like “UIView().layoutIfNeeded()” into a Swift file, and compile it, no Swift method call to layoutIfNeeded ever occurs.

This isn’t the case for all Cocoa types that are mapped into Swift. For example, imagine you wanted to break on all calls to “Data.write(to:options:)”. You might try to set a breakpoint on “Data.write” in the hopes that it works:

(lldb) b Data.write Breakpoint 11: where = libswiftFoundation.dylib`Foundation.Data.write (to : Foundation.URL, options : __ObjC.NSData.WritingOptions) throws -> (), address = 0x00000001044edf10

And it does! How about that? Only it doesn’t, really. This will break on all calls that pass through libswiftFoundation on their way to -[NSData writeToURL:options:error:], but it won’t catch anything that calls the Objective-C implementation directly. To catch all calls to the underlying method, you need to set the breakpoint on the lower level, Objective-C method.

So, as a rule, Swift programmers who want to be advanced debuggers on iOS or Mac platforms, also need to develop an ability for mapping Swift method names back to their Objective-C equivalents. For a method like UIView.layoutSubviews, it’s a pretty direct mapping back to “-[UIView layoutSubviews]”, but for many methods it’s nowhere near as simple.

To map a Swift-mapped method name back to Objective-C, you have to appreciate that many Foundation classes are stripped of their “NS” prefix, and the effects of rewriting method signatures to accommodate Swift’s API guidelines. For example, a naive Swift programmer may not easily guess that in order to set a breakpoint on the low-level implementation for “Data.write(to:options)”, you need to add back the “NS” prefix, explicitly describe the URL parameter, and add a mysterious error parameter, which is apparently how cranky greybeards used to propagate failures in the bad old days:

(lldb) b -[NSData writeToURL:options:error:] Breakpoint 13: where = Foundation`-[NSData(NSData) writeToURL:options:error:], address = 0x00000001018328c3

Success!

For those of you mourn the thought of having to develop this extensive knowledge of Objective-C message signatures and API conventions, I offer a little hack that will likely get you through your next challenge. If the API has been rewritten using one of these rules, it’s almost certain that the Swift name of the function is a subset of the ObjC method name. You can probably leverage the regex matching ability of lldb to zero in on the method you want to set a breakpoint on:

(lldb) break set -r Data.*write Breakpoint 14: 107 locations.

Now type “break list” and see the massive number of likely matches lldb has presented at your feet. Among them are a number of Swift cover methods that are part of libswiftFoundation, but you’ll also find the target method in question. In fact, you’ll also see a few other low-level Objective-C methods that you may want to break on as well.

To make the list more manageable, given your knowledge that the target methods are in a given Objective-C framework, add the “-s” flag to limit matches to a specific shared library by name:

(lldb) break set -s Foundation -r Data.*write Breakpoint 17: 8 locations.

Among these breakpoints there are a few false hits on the NSPageData class, but the list is altogether more manageable. The single breakpoint “17” has all of its matches identified by sub-numbers. Prune the list of any breakpoints that get in your way, and you’re good to go:

(lldb) break disable 17.6 17.7 17.8 3 breakpoints disabled. (lldb) c

Apple’s mapping of Objective-C API to Swift creates an altogether more enjoyable programming experience for Swift developers, but it can lead to great confusion if you don’t understand some of the implementation details, or how to work around lack of understanding. I hope this article gives you the tools you need to debug your Swift apps, and the Objective-C code that you are unavoidably leveraging, more effectively.

Update: I filed two related bugs: Radar #31115822 requesting automatic mapping from Swift method format back to underlying Objective-C methods, and Radar #31115942 requesting that lldb be more intuitive about evaluating terse Swift method signatures.